The Story of The Nelson-Atkins Museum

Courtesy: Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, MO.

Born from the visionary legacies of William Rockhill Nelson and Mary McAfee Atkins, The Nelson-Atkins Museum stands as a testament to the fusion of philanthropy and art, located in the heart of Kansas City.

Here, we explore its architectural splendor, significant expansions, and its evolution as a centerpiece of cultural and artistic expression in the heart of the city.

The Confluence of Dreams

Left: William Rockhill Nelson. Right: Mary McAfee Atkins.

Nelson, a prominent figure in the city's history as the founder of The Kansas City Star, was deeply influenced by the artistic wealth of Europe. His 1896 European tour catalyzed a passion for art, leading him to amass an impressive collection of fine art reproductions. His vision extended beyond his lifetime; his death in 1915 marked the beginning of an $11 million trust fund, dedicated to the expansion of Kansas City's art collection. This gesture of philanthropy was amplified by similar bequests from his family, showcasing a collective commitment to the arts.

Concurrently, Mary McAfee Atkins, a reclusive yet visionary widow of a real estate entrepreneur, was also touched by the grandeur of European galleries. In her will, penned in 1911, she allocated approximately $300,000 to establish an art museum. This amount, meticulously managed and bolstered by the economic growth of the era, grew to a substantial $700,000 by 1927. Her bequest, coupled with Nelson's, laid the financial groundwork for the museum.

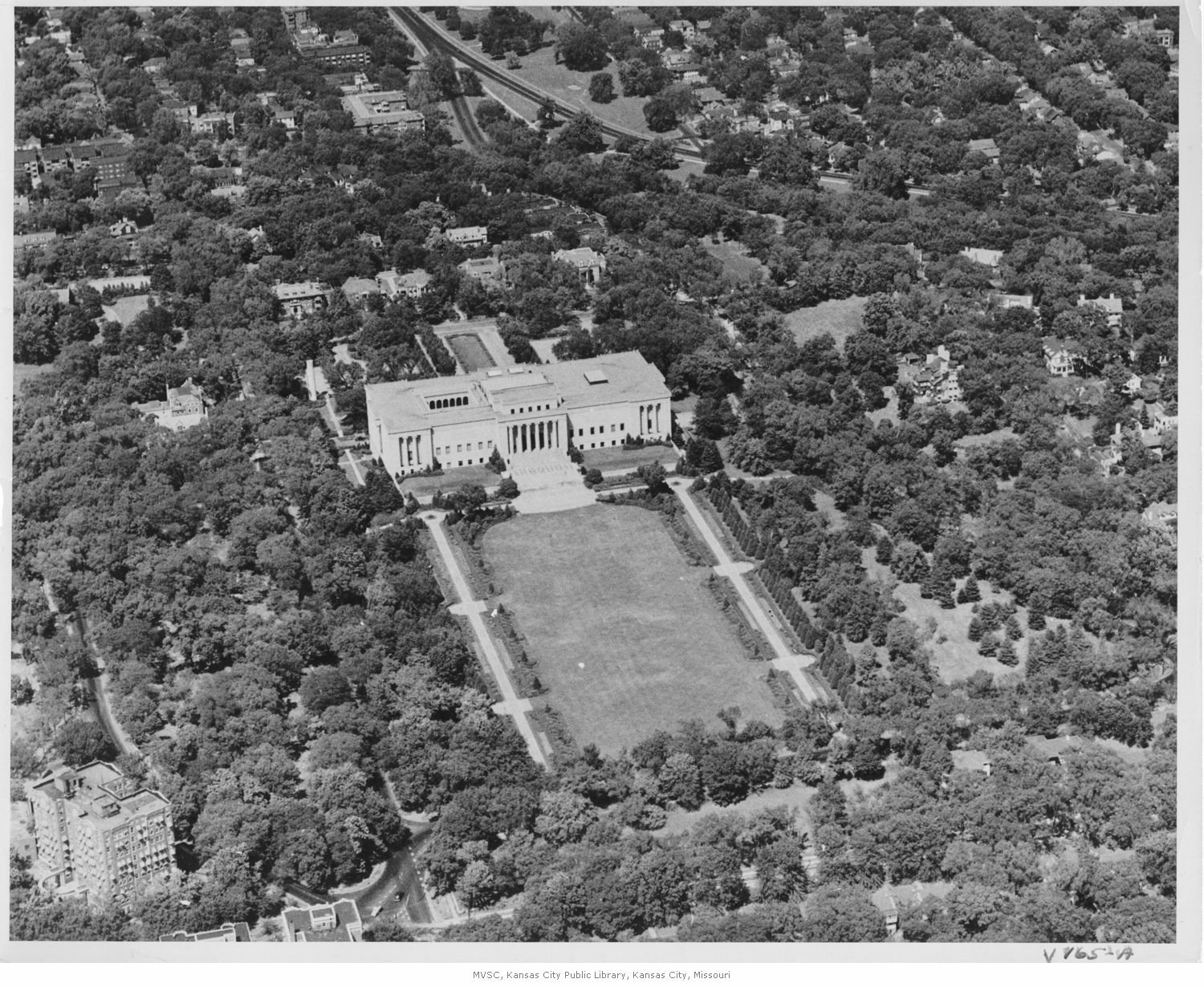

The initial plan for two separate museums evolved into a unified grand vision. Trustees overseeing both estates realized the potential impact of combining these resources. The decision was a landmark in Kansas City's cultural development, with the amalgamation of these funds creating a foundation for what would become a world-class institution. The Nelson family's Oak Hall estate was earmarked as the future site of this ambitious project, linking the museum's future with the city's past.

Architectural Elegance

Courtesy: Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, MO

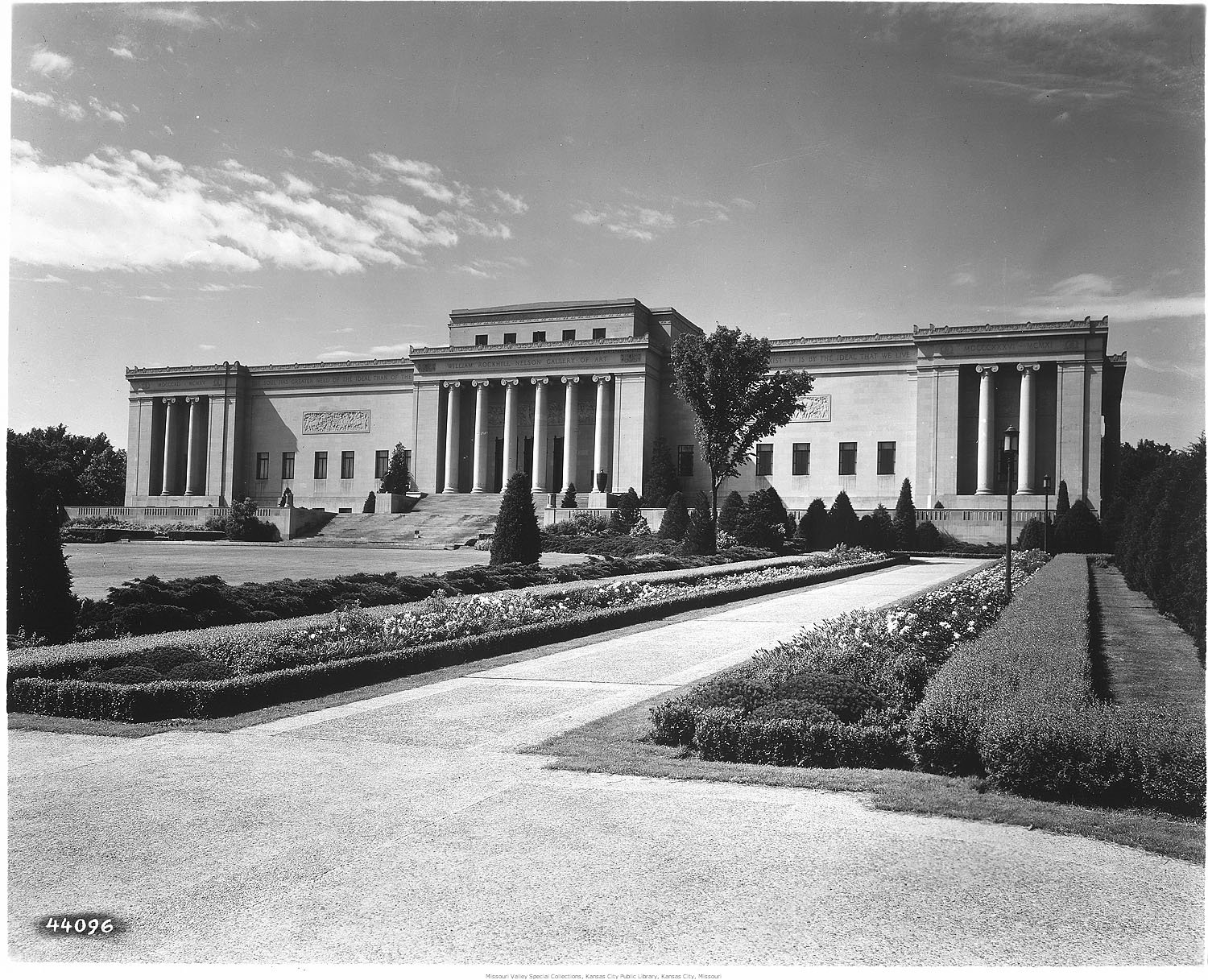

The responsibility of translating this grand vision into a tangible reality was entrusted to Wight & Wight, a firm that stood at the pinnacle of architectural excellence in Kansas City. The firm, guided by the specifications in Irwin Kirkwood's will and the prevailing architectural trends, chose a neoclassical design that symbolized the timelessness of art. The use of Indiana limestone was not only a nod to classical architecture but also a commitment to durability and elegance.

The design incorporated elements inspired by their international studies and other museums, notably the Cleveland Museum of Art. This inspiration was visible in the museum's prominent hilltop presence and its inviting garden court, which became a focal point for community gathering and reflection.

The construction process, which began with the razing of Oak Hall in 1928, was a blend of mourning for a cherished landmark and anticipation for the cultural enrichment it would bring. The museum's completion in 1933 unveiled a structure of monumental scale and beauty. The exterior was graced with towering columns and intricate details, including Charles Keck's limestone panels that narrated the march of civilization and bronze door panels depicting scenes from "Hiawatha."

The interior matched the exterior's splendor. Kirkwood Hall's towering black Pyrenees marble columns and the south vestibule's homage to a fifteenth-century Italian villa, designed by William Wight, showcased the museum's commitment to blending local and international artistic influences. The museum's initial collection, carefully curated to provide a historical panorama of art, included portraits from the English eighteenth-century school, reflecting the museum's goal of a diverse and comprehensive art narrative.

A Grand Unveiling

Courtesy: Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, MO

The crescendo of these intertwined dreams culminated in the inauguration of the Nelson-Atkins Museum on a momentous day, December 11, 1933. The museum's physical embodiment housed the Atkins Museum of Fine Arts within its east wing and the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art in the west. This dual identity persisted until a pivotal transformation in 1983, when the museum embraced a new name - the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. This rechristening marked the institution's commitment to nurturing the arts with unwavering dedication.

The latter part of the 20th century marked a new chapter in the museum's evolution. The turn of the millennium brought with it the need for expansion. This need was met innovatively by Steven Holl, whose architectural vision for the museum's expansion contrasted yet complemented the original structure. The Bloch Building, an underground marvel topped with glass pavilions, was a departure from traditional architectural styles. Opened in 2007, this addition not only increased the museum's capacity for displaying contemporary art but also signaled its commitment to modernizing while respecting its historical roots.

Holl's design, initially met with skepticism, eventually garnered critical acclaim for its architectural brilliance and its respectful dialogue with the original structure. This expansion was a physical manifestation of the museum's evolving role as a center for diverse artistic expressions and community engagement.

Bloch Building

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, in the 21st century, stands as a testament to the vision of its founders and the community's ongoing commitment to art and culture. Its policy of free admission, initiated in the late 1990s, reflects its dedication to accessibility and inclusivity. The museum embodies the enduring legacy of its founders, the transformative power of art, and the evolving narrative of Kansas City's cultural identity. This institution continues to inspire, educate, and resonate with diverse audiences, firmly establishing itself as an iconic part of the city's history and future.

Courtesy: Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, MO